I've run The Race each year since its first running,

in October 2018, and again last year

in October 2019. It's a great event, celebrating the African-American community in Atlanta and the Westside Atlanta neighborhoods on the official race route. With the COVID-19 pandemic, the organizer,

Tes Sobomehin Marshall, planned several months ago to pivot to a virtual race.

In the past week, I began reading "Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America" by Ibram X. Kendi, after he spoke last month in an Emory-hosted webcast. Following a discussion of his lecture in a chemistry department meeting, discussing more broadly what it means to be antiracist, a co-worker shared with me her recommendation of Prof. Kendi's book, published in 2016. I've only read the first few chapters, but it is a fascinating read. Even though I've already known the basic background of the origin of racism and slavery in the United States, it's interesting to read his in-depth analysis, and in the midst of chapter 3, I'm only up to the year 1657. I share some words from his prologue that brilliantly expressed a notion that I've realized in adulthood, and especially since I broadened my social circle and contacts through running:

"Anyone - Whites, Latina/os, Blacks, Asians, Native Americans - anyone can express the idea that Black people are inferior, that something is wrong with Black people. Anyone can believe both racist and antiracist ideas, that certain things are wrong with Black people and other things are equal. Fooled by racist ideas, I did not fully realize that the only thing wrong with Black people is that we think something is wrong with Black people. I did not fully realize that the only thing extraordinary about White people is that they think something is extraordinary about White people. I am not saying all individuals who happen to identify as Black (or White or Latina/o or Asian or Native American) are equal in all ways. I am saying that there is nothing wrong with Black people

as a group, or with any other racial group. That is what it truly means to think as an antiracist: to think there is nothing wrong with Black people, to think that racial groups are equal."

I certainly have been "stamped" with the idea that "something is wrong with Black people" and while I've fought that idea throughout my adult life, impressions that soak into one's brain early in life are difficult to shake off without conscious attention. This is where Prof. Kendi's writing is so valuable: he gives all of us a sentence that we can easily remember to counteract negative social programming: "There is nothing wrong with Black people as a group, or with any other racial group."

Even before I had begun reading Prof. Kendi's book, I had resolved to run The Race on a route through some of the historically African-American neighborhoods of Atlanta. I say "historically" because much of metro Atlanta is now desegregated, including people from White and other races living in virtually all parts of the city. I already knew from running parts of this route in recent years that while the majority of the people that I would see and encounter would be African-American, that I would also see and encounter people of other races including my own as I passed through the Westside and Southside neighborhoods. I also know that it wasn't always this way in Atlanta. The change has occurred within the 58 years of my life. I wasn't planning to run for time today, but instead to document my journey through photos, and then share my thoughts and impressions in this blog post. About half of the photos to come were taken today; the other half were taken when I ran a similar route four weeks ago, mostly to make sure that it was about a 13 mile loop and not too much longer.

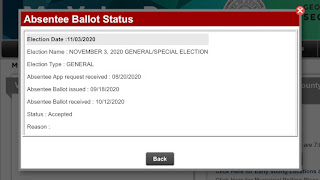

I parked on Edgewood Avenue, and warmed up on a pleasantly cool 50 degree morning by walking a few blocks to Auburn Avenue in the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historical Park. I took a few photos in the neighborhood while waiting for The Race to officially begin, tuning into the ChargeRunning App, which broadcasted and tracked our progress over 13.1 miles this morning.

At 7:40 am, just a few minutes after sunrise, The Race officially began! Running west on Auburn Avenue, I passed The King Center as the first Atlanta landmark. I wasn't able to stand far enough back to get the entire "Nonviolence or Nonexistence" logo engraved on the sidewalk, but you can get the idea from the photo below. After Ebenezer Baptist Church (where Congressman John Lewis' funeral was held in was held on July 30 - hard to believe it was more than two months ago), I passed under Interstates 75-85, where a mural depicting the area from the mid-20th century is painted on the walls of the underpass. I walked respectfully past the mural of Congressman Lewis, and then resumed my run, turning left on Piedmont Avenue. Scenes from mile 1 below:

On Piedmont Avenue, I passed a construction area for the expansion of Grady Memorial Hospital. This is our primary trauma center, and as a public hospital has long provided medical care to the uninsured people of our community. It is also one of metro Atlanta's hospitals currently dedicated to caring for seriously ill COVID-19 patients. The doctors and nurses and staff of Grady Hospital do absolutely essential work. Unfortunately I didn't know until this week, to quote Dr. Kendi, "What caused Atlanta newspaper editor Henry W. Grady in 1885 to produce the racist idea of 'separate but equal,' when he knew southern communities were hardly separate or equal?" Approaching the Georgia State Capitol, I was relieved to see that the National Guard was gone. On my runs in this area during the summer, they had occupied a couple of blocks in the area in a show of force, even though the legislature was out of session by then. Turning right onto Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, I ran through the nearly empty streets past the intersection with Peachtree Street to finish mile 2.

Continuing on MLK Drive approaching Mercedes-Benz Stadium, I enjoyed early morning view of downtown Atlanta buildings from the roadway passing over The Gulch. And on the south side of the stadium, I gave a couple of uncovered holes in the street my cold, hard stare. One of those nearly derailed my personal record-breaking performance in the

Atlanta Marathon on March 1! I couldn't help but wonder what

$750 in tax money might buy? Perhaps an hour or two of street repair and maintenance? (That is the last thing that I will write today that refers to a contemporary political person.) Photos from mile 3:

Running north on Northside Drive, past the Georgia World Congress Center, I came to the intersection with Ivan Allen Jr. Boulevard heading east, and Joseph E. Boone Boulevard heading west. In Atlanta, many streets change names as they cross the "color barriers" between historically Black and White neighborhoods, and I wondered if this was another example. The street has been renamed from "Simpson Street" in recent memory. Rev. Boone was an organizer of the non-violent movement to desegregate restaurants and department stores in the 1960's. Mr. Allen was Atlanta mayor during the same period, and although in his early political career he ran for office on a segregationist platform, during his years as mayor, his policies evolved to support desegregation, to testify before Congress in support of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and to support and honor Dr. Martin Luther King in the years prior to his assassination in 1968. I ran on Joseph Boone Boulevard through the Vine City neighborhood until I reached Kathryn Johnston Memorial Park. Ms. Johnston was a 92-year-old African-American life-long resident of Atlanta when she was killed in 2006 by thugs invading her home. She owned a handgun (yes, the Second Amendment also applies to Black people) and fired one shot toward the intruders before she was murdered in a barrage of 39 shots. She couldn't have known it until it was too late, but the intruders were police acting on a no-knock warrant.

The police attacked the wrong address. If only policies nationwide regarding no-knock warrants had changed after 2006. Maybe Breonna Taylor would not have been killed in Louisville, Kentucky in March 2020, under similar circumstances, while she was asleep in her home. From mile 4:

Now it was time to work my way to the northern terminus of the Westside Beltline. Passing the Ashby Station MARTA station, Lena Street was marked as part of the

PATH trail, which links many parts of metro Atlanta with protected walking and bicycle trails. I had no idea how many walking trails existed in Atlanta until I began running several years ago. And new trails open each year. Running past Booker T. Washington Park, I picked up my pace as the André 3000 - Outkast hit "Hey, ya!" played on the ChargeRunning app. This was a cross-over hit in 2003: to be blunt, "cross-over" means that it was OK for White people to like the song even though it was created and sang by a Black musician. That goes back to a message that I had absorbed as a child, that White people shouldn't listen to music by Black people. I was definitely poorer for that attitude, although I "rebelled" just a little as a teenager and occasionally enjoyed early hip-hop hits like "Rapper's Delight" by the Sugarhill Gang, and I recognized "Atomic Dog" by George Clinton when it was played on the ChargeRunning soundtrack shortly after I completed my 13.1 miles. I entered the Westside Beltline Trail just as the mile 5 alert sounded.

As I ran south on the Westside Beltline, I enjoyed views of MLK Drive passing through a residential neighborhood, and appreciated signs reminding us of the importance of physical distancing and mask-wearing. I don't wear a mask while running, but I deliberately choose places and times to run when the sidewalks are almost empty. Outside of my own little neighborhood, I always carry an Atlanta Track Club mask in a pocket of my running belt, in case I inadvertently get into a crowd or need to go inside a store for water and/or to use the restroom. I enjoyed some of the art on the Beltline, and took some encouragement from a message stenciled on an overpass for Interstate 20.

Art on the Beltline in this section included a little door, a characteristic art form all along the Beltline, and "Krayola" posts, which is one of my favorites. Overhead, there was a billboard reminding us of another viral epidemic, still awaiting a vaccine or a cure, even though it's been nearly 40 years since HIV / AIDS was first diagnosed. I realize that everyone under the age of 40 has never known a time without the fear of HIV / AIDS. After about a mile and a half, the Beltline crossed White Street, and then followed a wide sidewalk along White Street through the West End neighborhood for another half-mile. There's a discontinuous section of the Westside Beltline where you need to know to turn onto Mathews Street for a block, then left on Lawton Street, to get back onto the Beltline. Looking at the map, it must be a section where the Atlanta Beltline Partnership was unable to acquire the rights to the old railway, paralleling White Street. Near the end of mile 7, a runner came up behind me, recognizing my race shirt, and said "Great to see you're running The Race!" He was about my age, also running the half-marathon. Maintaining more than a six-foot distance, we chatted for a moment, I told him where I had started, and we exchanged names: he is Coach. I think that I've seen him before at runningnerds and other running events. He moved on ahead of me as I slowed to take some photos. Scenes from mile 7:

I crossed the overpass on Lawton Street and waited long enough to take Coach's photo as he re-entered the protected section of the Beltline. A couple of moments later, I was back on the Beltline as well. One of the Beltline projects is to grow trees and other plants all along the route. In front of the Best End Brewery, there is a new pond with pitcher plants growing within. There is a constant spray of water, which drew my attention. Passing a sign for the 2020 Census, where the finish line for the

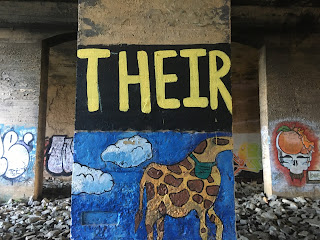

Monday Nighter 10K typically stands, I ran through the Lee Street underpass, where the Black Lives Matter slogan "Say Their Names" was painted on three consecutive columns. On the sidewalk, someone had written in chalk the Nelson Mandela quote "Action without vision is only passing time, vision without action is merely day dreaming, but vision with action can change the world." And near the end of mile 8, I passed under another outdoor art installation, which I can't describe, but it's the last of the photos below from mile 8:

At the beginning of mile 9, dozens of photos wrapped in plastic were attached to a fence bordering the Beltline. The photos were of Black victims of vigilante or police murders. There were more than I can list, but among the names I recognized Eric Garner, Emmett Till, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, Steve Biko, Tamir Rice, George Floyd, Freddie Gray, Breonna Taylor, Trayvon Martin, Malcolm X, James Chaney. Tears came to my eyes as I solemnly took photographs.

I resumed running, and soon reached the end of the Westside Beltline, which is under construction for connection to the unpaved Southside Beltline. In previous runs, I've found that the Beltline empties onto University Avenue. But today, the path was blocked by a fence. A couple of men were working on an electrical line in the area. I asked "How do I get to University?" and one of them replied, "You don't." I wasn't sure how far I would need to run back to find a cross-street, then saw a path through the grass that others must have used. Unfortunately it took me into an apartment construction zone, and I couldn't get past without walking through the restricted area, but at least the gate was open at University Avenue, and either no one saw me, or ignored me walking through. I remembered seeing this apartment complex two years ago: in October 2018, after completing The Race, I ran 9 more miles to complete my 22-mile long run in preparation for the

New York City Marathon in November 2018. Two years ago, the buildings were completely decrepit. I wasn't sure if anyone was living there, but I remember being a little scared and I got out of there as quickly as I could. I was delighted to discover a few months ago that the buildings were undergoing thorough renovation. The construction is not yet complete, but the apartments look quite nice from the outside. At the intersection with Metropolitan Parkway, I crossed into the Pittsburgh neighborhood.

As I continued to run along the narrow sidewalk of University Avenue, I spotted a sign for Keisha Waites, a candidate for John Lewis' 5th Congressional seat in the special election held last Tuesday. I began to smell barbecue smoke, and then I reached Zena's BBQ and Seafood Joint. Even though I no longer eat red meat, the barbecue smoke smelled really good. But I resumed running, crossing an underpass for Interstate 75-85.

A block after passing the interstate, there was a fenced empty lot. Until June, there was a Wendy's fast food restaurant at this site. On June 12, Rayshard Brooks fell asleep in his car while in the drive-through lane at the Wendy's. Atlanta police arrived, determined that he was intoxicated, and attempted to arrest him. He tried to flee on foot; he was shot twice by one of the policemen, and died shortly afterwards. The next night, the Wendy's was burned by a looter who had infiltrated a large group of protesters. Although I'm not saying that it was OK for Mr. Brooks to drink and drive, or to try to run away, neither of those things warranted shooting him. I imagine that he fled because he was afraid of the police, knowing that bad things can happen to Black men in police custody. What I just can't understand is, how can a policeman (or anyone else for that matter) just shoot another person after talking with him for 25 minutes? Doesn't that conversation create a human connection, even if you must arrest the person as part of your job? Just a few weeks after George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis on Memorial Day, how could any policeman not have been acutely aware of his own actions? Mr. Brooks wasn't anonymous. The police had his car. If they saw his driver's license, then they knew his name and where he lived. They could have found him using proper police techniques and properly and safely arrested him, probably within a few hours, instead of gunning him down.

Atlanta Magazine published an account from four different perspectives that was interesting for me to read.

I continued on my way. In a liquor store parking lot at the corner of University Avenue and Pryor Street, I saw an ancient blue Ford Falcon with badly faded paint job, but apparently still running. My parents had a 1965 Ford Falcon that they bought to have a more reliable car, right before my younger brother was born. I even remember learning to drive in it, shortly before my parents sold it in 1978. I ran south on Pryor Street for a block or two, passing under the railroad bridge before climbing the stairs to get back onto the Beltline, now the unpaved Southside Beltline, crossing the wooden path over the railroad bridge. I've added a photo of a 1965 Ford Falcon from the internet, and my photos from the last part of mile 10:

The abandoned railbed is gravel and you can even see some railroad ties in places. I tried to run along a line that was more dirt and less gravel. Shortly after getting onto the Beltline, the path went through a long tunnel under Hank Aaron Drive. On the other side of the tunnel, to the south of the Beltline there is a promontory which appears to have loft buildings on its top. Before I first ran this section of the Beltline about a year ago, I had no idea that all of this existed in the middle of our city. From mile 11:

At Boulevard Street, there was a grade crossing, then back into the wilderness. Within a half-mile, the path was closed. There was formerly an overpass here, at United Avenue, but I read that the overpass received too many strikes from large trucks, and

it was demolished in mid-summer 2020. Fortunately for me, the city (or the Atlanta Beltline Partnership) had installed stairs on either side of the demolished bridge, so I could keep going without another significant detour. To the left, off in the distance over a forest of weeds, I could see the cylindrical Westin Hotel, and some other downtown buildings. To the right, a rocket-shaped play structure dominated the skyline. Photos from mile 12:

I was still listening to the ChargeRunning broadcast, as some of the faster runners were finishing. I wasn't racing today - I've not mentioned any paces or times - especially with all of the stops to take photos, but the emcees began to call my name more frequently as I was approaching the "finish line". I began to run a little faster as Pharrell Williams upbeat song "Happy" was played.

(link to YouTube video of Congressman John Lewis dancing to "Happy" at a Stacey Abrams for Georgia governor campaign event in 2018) Then I just had to stop to take another photo of a cute little sign to Grant Park and also to the Labyrinth, which I should visit on my next trip through here. I resumed running an underpass at Berne Street near Beulah Heights University, where my father-in-law taught a business class on Saturday mornings a couple of years ago. I thought that I would run quickly for the last part of the unpaved Beltline, but stopped again to take a quick photo of a new art installation, which wasn't here when I ran this route 4 weeks ago. The ChargeRunning emcee was calling out my name along with Toni, mentioned that we were both in Atlanta, and speculated that we were running together. Actually I met Toni near the end of the

Summer Heat Half in July, which we both ran on the Silver Comet Trail in Cobb County. I had noticed on the ChargeRunning app that she and I were making about the same progress, but I had no idea where she was running today. Just as I was ready to finish strongly, I had to stop at Glenwood Avenue for a moment or two before I could cross the street. Then it was relatively slow going, stopping at multiple intersections. I crossed Interstate 20 again, now a few miles east of downtown. Photos from mile 13:

My watch had just recorded 13.00 miles as I approached Memorial Drive. I had to come to a full stop at a busy intersection, but then the ChargeRunning App chimed that I had apparently finished the half-marathon distance! (It tends to record a little bit short of true distance.) As I waited for the light to change, the emcee announced that Toni had finished, then called out my name as the next finisher. Across the street I could see that the old railway station was now a coffee shop. In the same moment, I recalled recently reading "Memorial Drive", a memoir from former Emory Professor Natasha Trethewey, who was also United States Poet Laureate during some of her years at Emory. I highly recommend this book, but it's a tragically sad account. To quote from the Apple Books review:

"Natasha Trethewey's deeply personal memoir is an indelible portrait of a scarring experience. Centered around the murder of her mother at the hands of an abusive ex-husband when Trethewey was 19,

Memorial Drive puts the horrific event in full perspective by building up the story that surrounds it, starting with her mother's marriage to her white Canadian father during the Jim Crow era in the Deep South - when antimiscegenation laws were still in effect. Trethewey, a former U.S. poet laureate, captivatingly recalls her life as a mixed-race child growing up in Mississippi and Georgia. From the Ku Klux Klan burning a cross in her family's driveway to her mother's eventual second marriage to a violently unstable Vietnam vet, Trethewey describes events in her life with stirring prose that makes every word feel like it was written in her own blood, sweat, and tears. Trethewey's poetic insight into the ways that racism in America has informed both her traumas and her reaction to them reminded us of Maya Angelou's

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. We won't be surprised if

Memorial Drive becomes a similar classic."

With the green light, I crossed Memorial Drive, and resumed running, now on the paved southern section of the Eastside Beltline. I wanted to "get full credit" on Strava for running the full 13.1 mile distance. I stopped my watch at 13.12 miles, and took a couple of photographs as I was entered the Reynoldstown neighborhood. With the easy effort and great weather today, I didn't feel beaten up like I might have if I had run faster, and had no trouble with a relaxed smile for my camera, even though my legs were a bit tired. Photos from the last 0.12 mile:

I walked for a few minutes while I typed congratulations into the text stream for the app to the other 117 participants, and a short thank you note to Tes for organizing The Race. Then I resumed an easy cooldown run to get back to my car, about a mile away from where I had finished. At the Krog Street tunnel, I snapped a few photos of graffiti. I will only post the one photo that isn't political, one honoring the late Kobe Bryant of the Los Angeles Lakers. I won't post the anti-Trump graffiti, because I promised earlier in this blog post, and somewhat inexplicably I feel sort of sorry for the president while he is currently battling his own infection with COVID-19. The final photo, on the north side of the Krog Street tunnel, is an homage to Rayshard Brooks.